WE TEND TO PREACH THE GOSPEL OF SOLAR POWER around here. If you’re going to use electricity, it’s the easiest, cheapest way to get it. As long as you have sunshine.

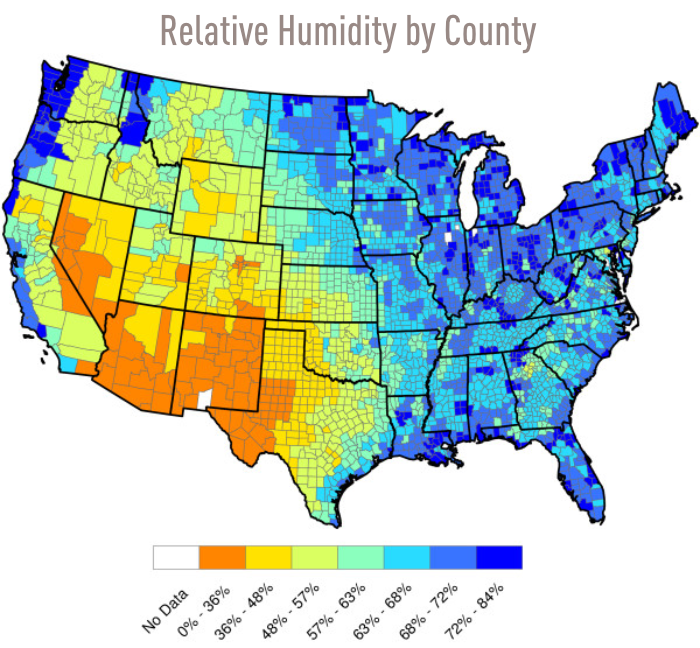

Oh. Yeah. Sunshine. That’s a less common commodity in some places. Take a look at the map above showing the average daily sunlight in the Lower 48. It’s not about the hours from sunrise to sunset, it’s about how much solar energy — kilojoules per square meter — makes it through the atmosphere and cloud cover to shine on solar panels. Parts of the country that tend to be cloudier, hazier, and more humid get less solar energy. Notice how the following map of relative humidity resembles the first map.

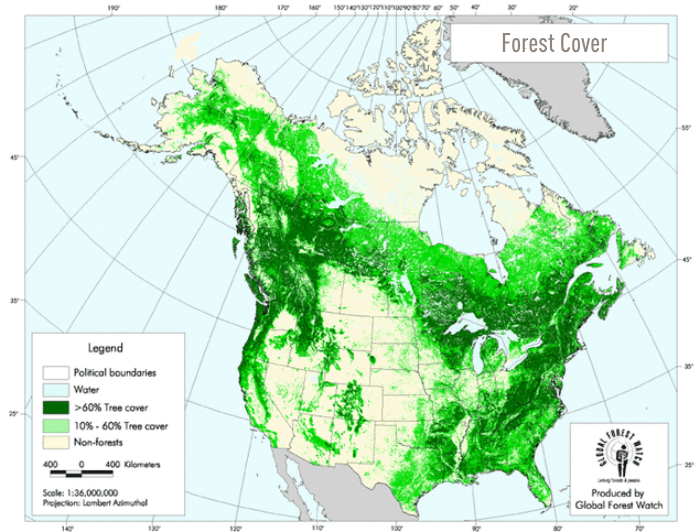

But water vapor (and particulate pollution) in the air isn’t the only thing reducing available solar energy. There’s also shade. All the lovely trees — even bare ones — get in the way. See how this map of tree cover is similar to the sunlight map.

What all this means is that collecting enough solar energy will always be more of a challenge in some parts of the country.

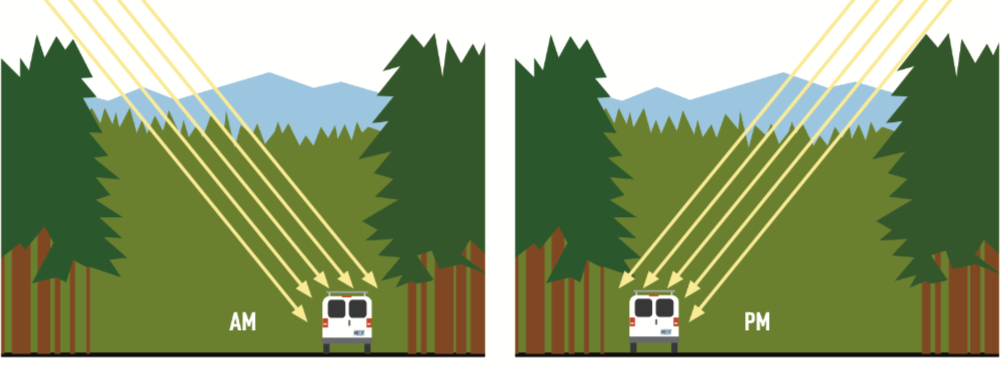

There was a time I was camped in a forest in Oregon. I had found a large clearing where, in order to maximize solar exposure, I would start the day on the west side of the clearing to catch the morning sun, then move to the east side to gather as much afternoon sun as possible. Back and forth. Back and forth. Fortunately, it was the middle of summer, the noon sun was almost directly overhead, and the sky was cloudless. Otherwise, I would need to leave camp every couple of days and find a sunny place to spend several hours while my batteries recharged.

A couple of my nomad friends have been dealing with sunlight shortage. They’ve both been in the forest in northern states this autumn, and both have said they’ve had to cut their visits short and move to parts of the country with fewer trees, less rain and more kilojoules of sunlight in order to keep their power stations charged.

Bob and I also tend to preach the gospel of desert boondocking. An abundance of sunlight is one reason. Those of you who prefer (or must be in) the red, purple, and black areas on the first map will have a more difficult time.

What can you do if you want to be in the lower sunlight areas?

Closely monitor how much power you have and how you use it. That’s especially true if you’re using a new electrical appliance for the first time.

More time in the sun and less time in the shade. Camp with as much open space as possible. Watch the weather and relocate to less cloudy locales if you can.

Angle your panels toward the sun and be diligent about repositioning them throughout the day to track the sun. I’ve visited campers in the afternoon whose panels were still in their morning position, which was now in the shade, because they got busy doing other things. If your panel is mounted to your rig, figure out a way to tilt it toward the sun, and accept that you’ll need to reposition your rig throughout the day or get by with less electricity.

More solar panels to grab more of the available sunlight. Whereas nomads in the yellow, orange, and red zones on the first map might get by with, say, a 150 Watt solar panel, you might need twice as much. Or more.

More storage capacity so the sunlight you do gather lasts long enough between good charges. That might mean more or larger batteries if you have a DIY solar power system, or a larger power station if you’re going that route. I know a guy who has two small power stations: the first one he thought would be enough, but wasn’t, and a second one for added capacity. He uses one while recharging the other, which is actually a good thing, because if you’re using power while trying to charge it takes even longer (in your diminished sunlight) to charge.

Use your vehicle’s electrical system to charge your house battery/power station while driving. But it takes a lot of driving to do that. Do you want to be driving several hours every day?

Use shore power to recharge. But that limits where you can be, and when.

And though I hate to say it, you might need a generator, either to recharge your battery or use directly. But there’s the cost of fuel, needing to store the fuel, and the fuel your rig burns to get more fuel, and the space to carry the generator. And it’s another machine that could go bad. Or get stolen. Oh, and there’s the noise.

So that puts me back in my pulpit, calling upon the congregation to forsake the darkness and come into sweet, beautiful, empowering light of the desert. Or at least to the treeless prairies.

A few years back we were with some people in northern Florida, after 3 days of clouds several pulled out the generators to refill the batteries, we had to use the vehicle engine. Using the engine works a LOT better if you’re driving..

I am clueless about electricity and that is what I hope to change by attending the 2023 RTR. I generally don’t use “appliances” but it would be great to have another source if I needed it.

Al, as I understood, to be able to tilt the solar panels aiming for the sun rays right angle it’s necessary to have a devise that allows to tilt them, isn’t it ? Hence if you don’t install that device from scratch, how will U be able to reorient the panels ?? Just saying…???

There are two situations here. The first is if you’re using a portable panel of some type set up on the ground. Naturally, you can pick that up and move it around. The second is if you have a panel mounted to your vehicle. Although it’s not necessary to have them mounted in such a way that you can tilt them, it’s a good idea and, yes, you would need to make that possible at some point. It doesn’t necessarily need to be done at the very beginning. I converted mine after a few months. Then a couple of years later I modified it to make tilting more convenient. But even if your panel doesn’t tilt, you might need to at least reposition the vehicle during the day in order to stay out of shadows.

I learned that highway driving charges faster than driving on city streets. When I spent a few months living in a facility’s parking lot, I would get on the highway on the occasional weekend and drive to Flying J primarily to recharge my batteries during the trip. Getting fuel while there might happen, too, but charging the batteries was the primary reason for the drive.

I love my abs. Thank you for those above

Not abs…”MAPS”.

Voice to text and software update = embarrassed.

I’m certain your abs are worth loving.

Al. ?????